Cuba has been my environmental hero since I went there in 2001. Here’s one example why:

[googlevideo]http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-66172489666918336[/googlevideo]

Category Archives: peak oil

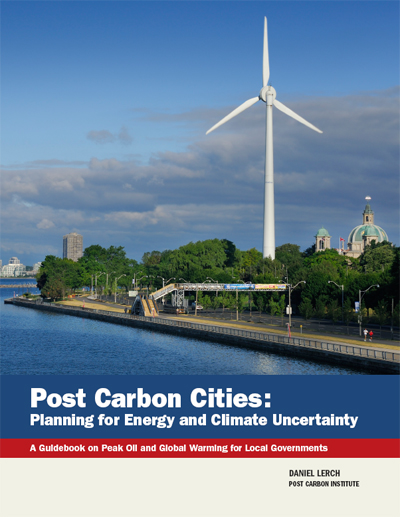

Post Carbon Institute

Post Carbon Institute was established in 2003 as an initiative of MetaFoundation, an organization created in the year 2000 by Julian Darley and Celine Rich. The purpose of MetaFoundation was to serve as an umbrella or parent organization, to help develop and support new organizations focused on innovative and unique methods of providing environmental solutions. The creation of MetaFoundation stemmed from an interest in- and concern for how difficult it is to cover complex environmental issues in current affairs. It was decided that new methods of discussing and addressing the complexity of environmental issues needed to be developed, and MetaFoundation was born.

The first initiative of Meta-Foundation was GlobalPublicMedia, an internet broadcasting station streaming long format audio and video interviews. This media service was established in 2001 in response to the tendency of mainstream news media to primarily focus on making a profit, increasing ratings and developing news as entertainment. Alternatively, the goal of Global Public Media is to offers news and analysis on complex environmental issues provided by world experts from a wide variety of different fields.

During the time GlobalPublicMedia was being developed, Julian was advised by a local bookseller to read Jeremy Rifkin’s book entitled ‘The Hydrogen Economy’. The last chapter of this book introduced the concept of ‘Peak Oil’ to Julian, leading to a profound shift in the focus and work of MetaFoundation.

After visiting Colin Campbell, a prominent petroleum geologist and founder of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil & Gas (ASPO) in Cork County Ireland, Julian and Celine embarked on a process of information gathering about Peak Oil. The expertise and comprehensive knowledge they attained during this time led them to establish the Post Carbon Institute, an environmental organization focusing on Peak Oil related issues.

With a keen interest base and their base of support coming out of the United States, it was decided that Meta-Foundation would be established as a nonprofit entity operating out of Eugene, Oregon. MetaFoundation was incorporated in 2003 with GlobalPubicMedia and Post Carbon Institute operating as affiliated initiatives, under the umbrella organizational format of MetaFoundation.

Over the next few years, with a growing public interest in the initiatives of Meta-Foundation, Post Carbon Institute was successful in establishing a reputable board of directors, featuring the most prominent experts working in the field of Peak Oil. With this new board with an increase in public interest, it was decided that Post Carbon Institute would replace MetaFoundation as the main umbrella organization. Today, Post Carbon Institute serves as the parent organization to many other initiatives and ideas, while MetaFoundation now operates as a legal entity only.

The blurb above is from their history page. We heard about them through Erin who heard about them on Public Radio in New Mexico. They also run a program called Post Carbon Cities. Visit the Post Carbon Institute and Post Carbon Cities by clickin’ them lanks.

Get ‘em When They’re Old, Too

Grandma vs. the Oil-Sands Mine

Eighty-five-year-old grandmothers aren’t typically subject to censorship, but Liz Moore is no ordinary grandma. After touring an oil-sands operation in Canada, Moore returned to her home in Colorado and began researching the mining process. Eventually, she spent $3,600 on a website that chronicles the destructive environmental impacts of oil-sands mining.

“I was appalled at what I saw—the devastation of the land,†she says of her visit to a Syncrude mine in Fort McMurray, Alberta. “I came home and decided people in the U.S. needed to hear about this, because we’ll be buying more and more oil from Canada.â€

Soon legal threats arrived. The mining giant Syncrude Canada Ltd. and a branch of the Alberta government threatened legal action if Moore did not remove certain photos from the website, she says.

“It made me angry at a very deep level,†Moore says. “I don’t like censorship, and if it’s done to me, I like it even less.†Moore later learned that a release she signed before her tour gave the company the right to limit the use of her photos.

Excerpts from Moore’s presentation:

To see the entire presentation, check grandma Moore’s website, oilsandsofcanada.com.

Untapped: The Scramble for Africa’s Oil

Salon.com has posted a great four part series of exceprts from the new John Ghazvinian book “Untapped: The Scramble for Africa’s Oil.” As with all Salon.com articles, if you’re not a subscriber you’ll need to view a short ad first, but it’s definitely worth it. From what Salon has posted, the book seems full of really important information about oil production in Africa that many of us are unfamiliar with – we’ve already ordered a copy off of Amazon

Some excerpts from Part 1, “Does Africa Live Up to the Hype?”:

Although Africa has long been known to be rich in oil, extracting it hadn’t seemed worth the effort and risk until recently. But with the price of Middle Eastern crude skyrocketing, and advancing technology making reserves easier to tap, the region has become the scene of a competition between major powers that recalls the 19th-century scramble for colonization. Already, the United States imports more of its oil from Africa than from Saudi Arabia, and China, too, looks to the continent for its energy security.

…one of the more attractive attributes of Africa’s oil boom is the quality of the oil itself. The variety of crude found in the Gulf of Guinea is known in industry parlance as “light” and “sweet,” meaning it is viscous and low in sulfur, and therefore easier and cheaper to refine than, say, Middle Eastern crude, which tends to be lacking in lower hydrocarbons and is therefore very “sticky.”

Then there is the geographic accident of Africa’s being almost entirely surrounded by water, which significantly cuts transport-related costs and risks. The Gulf of Guinea, in particular, is well positioned to allow speedy transport to the major trading ports of Europe and North America. Existing sea-lanes can be used for quick, cheap delivery, so there is no need to worry about the Suez Canal, for instance, or to build expensive pipelines through unpredictable countries.

A third advantage, from the perspective of the oil companies, is that Africa offers a tremendously favorable contractual environment. Unlike in, say, Saudi Arabia, where the state-owned oil company Saudi Aramco has a monopoly on the exploration, production, and distribution of the country’s crude oil, most sub-Saharan African countries operate on the basis of so-called production-sharing agreements, or PSAs. In these arrangements, a foreign oil company is awarded a license to look for petroleum on the condition that it assume the up-front costs of exploration and production. If oil is discovered in that block, the oil company will share the revenues with the host government, but only after its initial costs have been recouped. PSAs are generally offered to impoverished countries that would never be able to amass either the technical expertise or the billions in capital investment required to drill for oil themselves. For the oil company, a relatively small up-front investment can quickly turn into untold billions in profits.

Yet another strategic benefit, particularly from the perspective of American politicians, is that, until recently, with the exception of Nigeria, none of the oil-producing countries of sub-Saharan Africa had belonged to the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)…The more non-OPEC oil that comes onto the global market, the more difficult it becomes for OPEC countries to sell their crude at high prices, and the lower the overall price of oil. Put more simply, if new reserves are discovered in Venezuela, they have very little effect on the price of oil because Venezuela’s OPEC commitments will not allow it to increase its output very much. But if new reserves are discovered in Gabon, it means more cheap oil for everybody.

But probably the most attractive of all the attributes of Africa’s oil boom, for Western governments and oil companies alike, is that virtually all the big discoveries of recent years have been made offshore, in deepwater reserves that are often many miles from populated land. This means that even if a civil war or violent insurrection breaks out onshore (always a concern in Africa), the oil companies can continue to pump out oil with little likelihood of sabotage, banditry, or nationalist fervor getting in the way. Given the hundreds of thousands of barrels of Nigerian crude that are lost every year as a result of fighting, community protests, and organized crime, this is something the industry gets rather excited about.

All these factors add up to a convincing value proposition: African oil is cheaper, safer, and more accessible than its competitors, and there seems to be more of it every day.

Part I: Does Africa Live up to the Hype?

Part II: Yes, We Have No Bananas

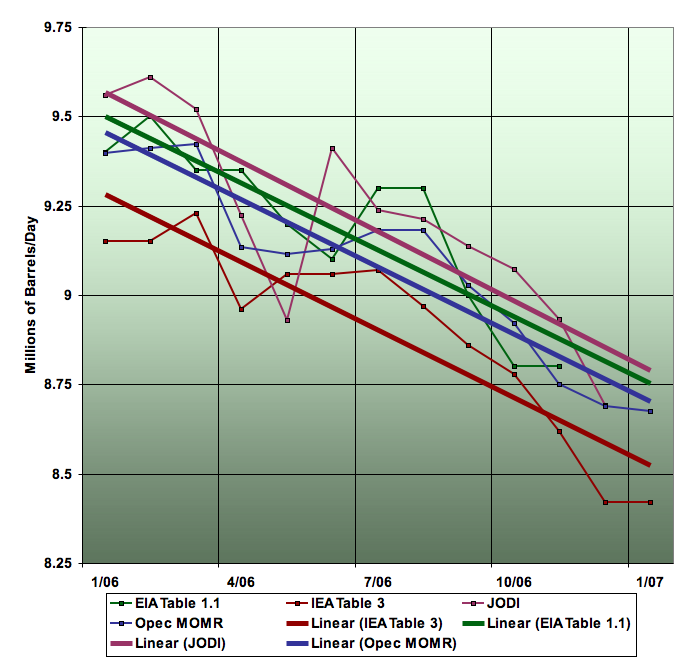

Saudi Arabian oil declines 8% in 2006

“At that time, while the conjunction of declining production and rising rig counts was striking, I wasn’t ready to draw firm conclusions on the data through August-October (depending on agency). Recently, Jim Hamilton raised the same questions:

The first possibility is that the Saudis could still pump 10 mbd or more today if they wanted to, but they are cutting back production and exploring like mad because they put an extremely high value on having 2-3 mbd of excess capacity. If so, the recent price behavior suggests that the reason they would seek such capacity is not because they want to stabilize the price, but because it puts them in an incredibly powerful negotiating position. For example, the ability at any time to flood the market could be used at an opportune moment to undercut expensive alternatives such as oil sands that require an oil price over $50.

The second and more natural interpretation is even more disturbing: the mighty Ghawar oil field is already in decline, and the Saudis don’t want anyone to know.

…

Overall, I feel this data is clear enough that I’m willing to go out on a limb and conclude the following:

- Saudi Arabian oil production is now in decline.

- The decline rate during the first year is very high (8%), akin to decline rates in other places developed with modern horizontal drilling techniques such as the North Sea.

- Declines are rather unlikely to be arrested, and may well accelerate.

- Matt Simmons appears to be right in Twilight in the Desert, but the warning did not come until after declines had actually begun.”

Oil Innovations Pump New Life Into Old Wells

Are Reports of Oil’s Demise Greatly Exaggerated?

In Indonesia, Chevron has applied the same technology to the giant Duri oil field, discovered in 1941, boosting production there to more than 200,000 barrels a day, up from 65,000 barrels in the mid-1980s.

And in Texas, Exxon Mobil expects to double the amount of oil it extracts from its Means field, which dates back to the 1930s. Exxon, like Chevron, will use three-dimensional imaging of the underground field and the injection of a gas — in this case, carbon dioxide — to flush out the oil.

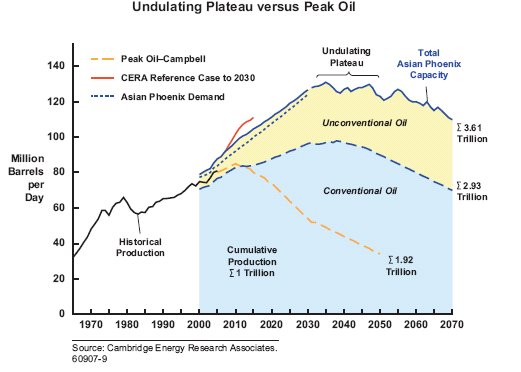

Within the last decade, technology advances have made it possible to unlock more oil from old fields, and, at the same time, higher oil prices have made it economical for companies to go after reserves that are harder to reach. With plenty of oil still left in familiar locations, forecasts that the world’s reserves are drying out have given way to predictions that more oil can be found than ever before.

“It’s the fifth time to my count that we’ve gone through a period when it seemed the end of oil was near and people were talking about the exhaustion of resources,†said Daniel Yergin, the chairman of Cambridge Energy and author of a Pulitzer Prize-winning history of oil, who cited similar concerns in the 1880s, after both world wars and in the 1970s. “Back then we were going to fly off the oil mountain. Instead we had a boom and oil went to $10 instead of $100.â€

There is still a minority view, held largely by a small band of retired petroleum geologists and some members of Congress, that oil production has peaked, but the theory has been fading. Equally contentious for the oil companies is the growing voice of environmentalists, who do not think that pumping and consuming an ever-increasing amount of fossil fuel is in any way desirable…

[NYTimes]

Does the Peak Oil “Myth” Just Fall Down?

The editors of The Oil Drum respond to Why the “Peak Oil” Theory Falls Down — Myths, Legends and the Future of Oil Resources by Peter M. Jackson, Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA)

We are concerned that CERA has “maintained a consistent contrary view” and not taken the peak oil hypothesis seriously until now. We can only agree that “this debate reflects one of the most important issues facing not only the energy industry, but the world at large.” We hope our response demonstrates that the peak oil hypothesis is anything but simplistic. Furthermore, no one here or elsewhere is claiming that conventional oil will “run out” anytime soon. Rather, the peak oil view is an evolving, sophisticated take on conventional oil production and the viability of substitutes to replace continuing demand for this paramount fossil fuel in the face of inevitable declines in available supply. Only the timing of such declines is at issue here. We can also only add that denial in the face of potentially very threatening events is a powerful force in the human psyche.

Peak Oil?

A great (and balanced) documentary series from Australia on Peak Oil